About Egyptian Dance

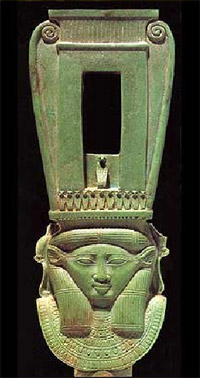

The Naos Sistrum — Old Kingdom, used exclusively in ritual and particularly associated with Hathor.

The Naos Sistrum — Old Kingdom, used exclusively in ritual and particularly associated with Hathor.

A Synopsis

BCE

The information we have on the daily existence and religion of ancient Egyptians has been derived mainly from monumental, representational and textual evidence still extant into the 19th Century. Much of the evidence is sketchy and therefore open to conjecture and this is especially so in relation to ancient Egyptian dance. How a dance may have looked in its entirety, or in fact what it may have represented remain speculative.

Recent work by Leslie Kinney on 'Visually communicating the passage of time in ancient Egyptian wall art', examines several techniques used by ancient Egyptian artists to depict sequential time and movement in wall art.

This multiple mode thesis offers a glimpse of ancient Egyptians performing movement through time and space, as well as providing insights into how Egyptian wall art may be interpreted.1

- The animated illustrations of Lesley Kinney's research may be viewed at galliform.bhs.mq.edu.au/edg/dance.html Published The bulletin of The Australian Centre for Egyptology Volume 18.

Ritual

What remains constant is that ancient Egyptian religion included many elaborate and exacting rituals created to appeal to an intricate pantheon of Gods and Goddesses, with the most vital of these rituals being performed away from public view. This was considered necessary in order to preserve the sacred purity of the act and therefore ensure the success of the ritual.

Special troupes were formed and trained specifically for ritual, and these men and women are referred to in surviving Old Kingdom text as 'musical troupes' - 'Khener'.

In the Old Kingdom it seemed the troupes were exclusively composed of women - and could also be overseen by a woman. However by the Middle Kingdom men were predominant in the role as overseer, and male musicians and singers also appear to have been included in these troupes toward the end of the Old Kingdom.

In the New Kingdom priests officiate under the supervision of the head priest, whilst priestesses provide the ritual music/dance headed by the 'Weret Khener' - 'great one of the troupe of musical performers'2. This prestigious post was conferred to women of high status, and specifically referred to their role as overseer of the musicians of the cult. She was usually royalty or a close relative of a high ranking priest or official. Although men also participated as musicians and singers, they were usually not named specifically in text and therefore it is assumed they were not of high rank.

Over time the increasing complexity of rituals necessitated that trainees be retained by temples. The more powerful a particular cult, the more likely musical troupes could afford to be retained and trained for the exclusive use of a temple.

In other cases musical troupes could find patronage through royal and private households and also serve their designated temple, therefore being conveniently available to entertain the elite at any time. Those who did not have the means to engage musicians on a regular basis could use servants. Daughter or wives may also oblige, although it seems the higher the status of the family or individuals involved the less likelihood there was of this occurring — except in the case of ritual.

Secular Entertainment

The elite of ancient Egypt were entertained at sumptuous banquets with music, dance, food, wine and beer, which they merrily drank in copious quantities until unashamedly incoherent, ill or both. Inebriation seemed to have also played an important part in communion with certain Gods.

The performances ranged from solemn to very lively and included acrobatics, wrestling, historical tableau, mythological/religious depictions and pygmies. It would appear pygmies were also critical to certain ritual and therefore particularly prized. Imported from the headwaters of the Nile at the instigation of various pharaohs, they were given the appellation 'Dance Dwarfs of God' signifying their importance in the court of Pharaoh. One theory is that they were considered a manifestation of the dwarf god Bes, a particularly fearsome spirit3, whose carved form was used everywhere in the home to ward off evil spirits, particularly during child birth and also protect children. Due to a commonality in certain powers, Bes has also been associated with the goddess Hathor4. Dancers dedicated to Hathor had a picture of Bes tattooed on their inner thighs.

Mirrors of copper or brass would have been highly polished to reflect the beauty of an Egyptian lady.

Mirrors of copper or brass would have been highly polished to reflect the beauty of an Egyptian lady.

Although dance, music, song and chant are evident throughout ancient Egyptian life, dance was especially important to the cults of Hathor and Bast. To Hathor dance was 'food for the heart'5.

One particular dance attributed to the goddess Hathor required the dancer to hold a mirror with one hand whilst reflecting the image of her free hand or a hand shaped object6.

Asiatic dancing girls were introduced during the invasion and occupation of the Hyskos (1700)BC. The Hyksos were Semitic tribes originally believed to be from Palestine and Syria. It is here that the sharp angular lines previously depicted begin to soften, and a gentler, flowing art form is introduced. The Hyksos were also credited with introducing the long necked lute, lyre, oboe and tamborine. The harp dates from the Old Kingdom and by the Amarna period it was so large that two people were required to play it. The flute is one of the oldest instruments in the continuum of Egyptian instruments.

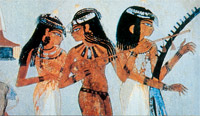

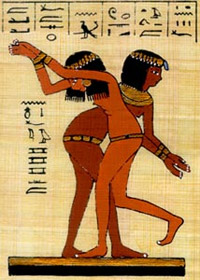

18th Dynasty musicians

18th Dynasty musicians

An extant report from Memphis in the 4thC BCE describe African dancers performing 'a rumba-like…(dance)… unquestionably erotic in character'7 - suggesting to scholars that Belly Dance may be African in origin. African women still exhibit a dance style that is consistent with this description. There is however extant evidence that reveals an even more likely source for the Belly Dance of today; for more on this subject see About Belly Dance.

A depiction on a tomb wall (circa 1400 BCE) shows female musicians accompanying two adolescent female dancers. The dancers depicted are naked with the exception of a hip girdle, they have rounded arms and appear to be passing one another with a swooping gesture. This motif of the naked adolescent female appears on tomb walls from the 18th Dynasty and depicts the girls in various activities: serving their mistress, dancing or playing a musical instrument. The motif is also found on various items recovered in tombs - especially ritual spoons, mirrors and bowls. It is believed from the manner in which these adolescent servant girls are depicted that the images were also associated with Bes/Hathor: fertility, childbirth and rebirth.

In summary Ancient Egyptian entertainment was stimulating, skilful, diverse and visually rich, with music, song and dance playing a crucial role in both ritual and daily life. Dance and artistic expression was informed by religion, the socio/political environment - trade, conquests and invasions - and reflected the many facets of a rich and extraordinary culture.

- Women of Ancient Egypt — G. Robbins — pg.148

- The dancers often wore a mask of a fearsome lion, tail, feathered head dress. On other occasions Bes could also appear as a jovial almost comic chap.

- i.e. fertility, sexuality, childbirth

- 'Gods and Symbols of Ancient Egypt'

- The use of both hand and mirror is what led scholars to consider a link with Hathor. The female potential of the creator God, (that is to say the female-male aspect of Amun-RE, which enabled him to create the first divine couple), came to be identified as ‘The God’s Hand’, which eventually became synonymous with the goddess Hathor, whose duties included assistance in fertility, sexuality, child birth, beauty, dance and music. The mirror depicted in the dance is linked to Hathor by virtue of its solar shape.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica — The history of Western Dance.

CE

The first millennia opened with the Roman occupation (30BCE-395CE), overlapping the introduction of Coptic Christianity (c43-648) and from 395 to 639 Egypt fell under the Byzantine Empire (following a split with the Roman Empire).

A Persian occupation from 618 (lead by Chosroes II) was short lived with the Byzantine Empire regaining power (629 - 639), only to meet with the invading Muslim armies — These Arab invaders heralded the spread of Islam in Egypt (from 639 onwards), through a long succession of Caliphs. This was interrupted in 1798-1801 by Napoleon Bonaparte and the French occupation - Bonaparte was ousted initially by the British - who inturn were driven out by the ambitious Albanian lieutenant (Mohammad Ali) - at the head of an Ottoman army. Through some wily political machinations, Mohammad Ali and his descendants (1804 - 1952) ruled as hereditary pashaliks and finally in 1867 acquired the title of Khedive. The British returned from 1882-1952 first with occupying forces then as Protectorate.

Finally the Socialist revolution of 1952, restoring Egypt to independent rule after over 2000 years of successive occupation.

Take a breath and dance on…

It would be correct to assume that during this period the arts and dance experienced equal periods of flux and extraordinary transformation – particularly in the major cities to the North of Egypt.

Although creating opportunity for new artistic expression, the socio/political/religious changes also frequently placed restrictions on artists and particularly on dance. During the more difficult and oppressive times survival of such traditions was reliant on those who already dwelt on the fringe of society, and/or were situated well away from the major cities.

- This is according to the Church of Alexandria, however no archaeological evidence to corroborate this date has been found to date. An letter dated c160-215 from Clement, (bishop of Alexandria) claims Saint Mark came soon after the martyrdom of Peter in Rome (64) - the authenticity of this letter is in dispute. The earliest archaeological evidence that has been uncovered in Alexandria dates to 200CE. This is not surprising as the site of the city of Alexandria (approx. 5km E/W and 2km N/S) has been consistently built upon since it was founded by Alexander the Great in 332BC).

19th Century

Napoleon Bonaparte's ill-fated foray into Egypt acquired a new spin on his return to France via his bestowing upon the French citizens an extraordinary array of exotic images and accounts.9 The collective studies of the scientists, artists, historians and engineers who accompanied Bonaparte ignited a European fascination for ancient Egypt that lead to the deciphering of hieroglyphs, the advent of Egyptology as an academic pursuit and archaeology as the regulated scientific discipline it is today.10

Jean Leon Gerome

Jean Leon Gerome

French soldiers who mixed with the 'dancing' girls also came home with tales - mostly X rated. The women with whom they were able to socialize were principally prostitutes, who used 'dance' solely as a means of attracting custom. Respectable women and artists were kept well away from the gaze and attentions of the 'infidels'.

In fact, fearing they may be forced to perform for the French, the genuine Egyptian artists had already left the capital.11

In 'The Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians' (1833,35) by Edward Lane, there are accounts of an entertainer tribe referred to as Ghawazee.12 This tribe (of numerous branches) were prolific in number and scattered throughout Egypt, living in specific areas or 'quarters' in every major town and city. In the street they dressed as other Egyptian women — with one major exception — they did not wear a veil. This alone was enough to cause them to be marginalised, however according to Edward Lane they existed in relative harmony within daily Egyptian life.

The Ghawazee13, claimed not to be Egyptian, but descendants of the renowned Baramakids14. This claim was not given serious consideration due to their low circumstance and choice of occupation — dance and prostitution.15

However Lane concedes that 'by a cast of countenance differing, though slightly, from the rest of the Egyptians, we can hardly doubt that they are, as themselves assert, a distinct race'.

Ghawazee Circ 1800

Ghawazee Circ 1800

They performed mainly in the streets, outside cafes or in the courtyards of private houses, rarely being invited into a respectable home to perform.

A few of their number would also sing and displayed a standard of talent and such pleasing appearance, as to be compared favourably with the Awalim16 and often travellers not having an understanding of the cultural arts would assume the Ghawazee were the illustrious Awalim – savants of Arabic music, poetry and song.

It is equally likely that the distinctions were not made clear to travellers by the entertainers wishing to secure work.

An early Egyptologist Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (1797-1875) provides us with an eye witness account: c mid1830’s:

"Esne has become the place of exile for all the Almehs and other women of Cairo, who offend against the rules of the police, or shock the prejudices of the Ulemas (the doctors of law . . . the priests of Islam). The learning of these 'learned women' has long ceased; their poetry has sunk into absurd songs; their dancing would degrade even the motus Ionicos of antiquity; and their title Almeh has been changed to the less respectable name of Ghowazee, or women of the Memlooks."18

Ghawazee

Ghawazee

Perceptions of the Ghawazee traditions suffered similarly as women who perhaps did not dance professionally, but who were exclusively prostitutes, would take the attitude of a dancer if that is what was required – this decline of standard and tradition was commensurate with Western interest.19 The fact that various tribes and gypsies shared the same city quarter as the Ghawazee would have made possible the melding of costuming, attitudes and opportunities, further adding to the confusion as they all vied for opportunities.

It should be noted that the Ghawazee themselves do not claim to be of gypsy origin, but due to their (somewhat) makeshift abodes and constant travel for work at mulids and other festive occasions along the Nile it became an observers assertion that they were Gypsies.20 Thus today whenever referenced they are freely and frequently referred to as a 'gypsy' tribe.

'Almeh' — Gerome

'Almeh' — Gerome

The European artists' depictions of women in languid, submissive attitudes - either alluringly veiled or partially if not wholly undressed, conveyed an Orientalist perspective addressed by Edward Said in his book: 'Orientalism'. European travellers of the 19th C openly sought such images and performers for their personal gratification, and frequently made utter nuisance of themselves by demanding dancers perform either similarly disrobed or naked.21

Lucie Duff Godon wrote from Egypt in1836:

"Seyyid Achment (her host) would have given me a fantasia, but he feared I might have men with me, and he had had a great annoyance with two Englishmen who wanted to make the girls dance naked, which they objected to, and he had to turn them out of his house after hospitably entertaining them."

There are accounts of some dancers complying with these requests, but generally after negotiation22 and substantial payment. In fact a kind of pantomime dance was created around this time to accommodate these demands, which afforded the dancer some sense of control in the proceedings. Referred to as the 'Dance of the Bee', the dancer would begin in a composed state dress layered in several veils. As the dance progressed the dancer would become more agitated and vigorous in her movements as she progressively removed each veil, ostensibly searching for a bee or wasp concealed somewhere within the folds. It has been suggested this may be the earliest documented account of strip-tease and, it would seem to me, a plausible inspiration for the later theatrical renditions of Solome’s dance of the seven veils.23

These images of the east — along with the ribald reports — attracted adventurers of a decidedly undesirable nature to Egypt. In order to assuage the escalating concerns and complaints of both citizens and especially religious bodies, the governing Pasha — Mahommad Ali, had dance and prostitution outlawed.24

From 1834 to be caught dancing or soliciting attracted harsh punishment: first offence: 50 lashes; second offence: more lashes and hard labour for one or more years, followed by exile to the South of Egypt.25

- This is according to the Church of Alexandria, however no archaeological evidence to corroborate this date has been found to date. An letter dated c160-215 from Clement, (bishop of Alexandria) claims Saint Mark came soon after the martyrdom of Peter in Rome (64) - the authenticity of this letter is in dispute. The earliest archaeological evidence that has been uncovered in Alexandria dates to 200CE. This is not surprising as the site of the city of Alexandria (approx. 5km E/W and 2km N/S) has been consistently built upon since it was founded by Alexander the Great in 332BC).

- (1798-1801)

- Modern Egyptology, is generally dated to 1822 when François Champollion deciphered the enigmatic hieroglyphs.

- Villoteau 1822 (A trade like any other — pg.30)

- Ghawazi (plural- also spelt Ghawazee); Ghaziya (Female singular); Ghazyi (Male)

- singular — Ghazeeyeh

- The Barmakids were of Persian descent who enjoyed high status as Vizers under the Abbasyid dynasty. For possibily a variety of reasons they fell out of favour of the Caliph Harun Al Rashid, and those members of the Barmakids clan who were not immediately killed or imprisoned were forced into exile.

- It could be disputed whether all Ghawazee dancers were originally prostitutes, even though most accounts seem to state so, as another tribe of mixed Berber heritage known as the Oulid Nails had for centuries existed as a matriarchal tribe using prostitution and dance as their main source of income. The Oulid Nails tribal mores and social customs so resembled that attributed to the Ghawazee by earlier travellers accounts, as to call into the question the blanket term 'prostitute' placed over every Ghawazee dancer, especially in light of the fact few early travellers spoke the language, their exposure was not extensive and the ‘study’ therefore not exhaustive. Also it should be noted that much of the written accounts of travellers came in the early to mid 1800's, and by then traditions and the dance itself was already heavily corrupted.

- Awalem: plural (learned women — savants of Arabic music, poetry and song), singular: Almeh

- Lucie Duff Gordon

- In this description Wilkinson gives us a clue as to the possible origins of the Ghawazee in Egypt

- One positive outcome of the banishment to the south was the fact the dancers formed alliances with traditional Sa'idi musicians with whom they performed, married and settled. Although considered low class by the elite because they are away form the cities, (all that is considered progressive and desirable), their knowledge has formed the basis for the revival of folk and the inspiration for many of the choreographies that we see in the Cultural performance arts of Egypt.

- Some Ghawazee had well established homes, but most lived as described – in tents and relatively make shift homes.

- LUCIE DUFF GORDON: on European travellers: 'The English have raised a mirage of false wants and extravagance which the servants of the country of course, some from interest and others from mere ignorance, do their best to keep up'.

- Including blind-folded musicians

- Seven being synonymous with the (7)gates the Babylonian goddess Ishtar must pass to gain access to the underworld. Her admission through each gate was allowed only after the removal of a piece of clothing or jewellery. Thus loosing all those emblems of material status to enable the revelation of 'self'.

- 1834 - Apparently the ban was difficult to enforce outside Cairo, and in any case travellers were soon following the dancers to the South. The ban was lifted by the 1850's, - however restrictions and heavy tax levies applied. — see about Belly Dance

- Edward Lane — Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians

20th Century

The British Occupation and protectorate (1882-1952) heralded even greater challenges — particularly in Cairo — due to an influx of Fellahin26 seeking opportunities from the changing eco/political conditions.27

Baladi wedding led by the 'fitoowah' C mid1800's

Baladi wedding led by the 'fitoowah' C mid1800's

Along with them came their rural songs and dance traditions which found an easy compatibility with the Western jazz and blues genres and soon a new dance and music tradition was formed: Baladi.28 — 'Of my country' or 'my country' — Baladi dance, music and song epitomized city savvy, but was also filled with a nostalgia and longing for the values of the past.

Although blending some Western elements, the artists and composers of Baladi music and dance did not lose sight of those aspects that were considered quintessentially Egyptian in character.

The early 20th Century also saw a gradual shift from the long held tradition of a professional troupe, (headed by the Usta29) to that of the bejewelled Belly Dancer. The single show girl performing for a new type of audience in a new type of venue — the Salas (nightclub) — where food and alcohol could be served along with the entertainment provided. The entertainment in these clubs was designed to encourage the consumption of alcohol and the term 'fath'30 entered the Egyptian/Arabic vernacular.

For a more complete history of the advent of Belly Dance in the 20C see About Belly Dance

Following the Revolution of 1952 and independence, Egypt experienced a renewed surge of National pride. So where was the National Dance? The opportunity to create a dance company that reflected the cultural traditions, sensibilities and collective experience was clearly already overdue. This period of reclamation was mostly accomplished through the support of those artists who still exhibit links to their traditions, in their music, musicianship and dance expression — and they were found in the south of Egypt. However in an effort to continue to appeal to European tastes and attitudes, many choreographies and costumes had as much in common with Eastern European dance than Egyptian movement, dress and expression.

In the last 20 years in particular there has been a revival that has developed free of the 'cultural recoil' that has previously infused attitudes, interpretations and expressions toward the indigenous traditions. Although being 'of the soil' was considered déclassé and therefore undesirable, particularly during modernisation, the simple values and innate strengths portrayed in the achetypes of the Awlad El Balad — 'Children of the Country' — are now increasingly lauded as desirable traits.

- Farmers/peasants — people from the land

- Western cash flow in particular

- See 'About Baladi' Essay

- The Usta (singular) (ustawat - plural) was an appellation given to a women who headed of a group of performers who entertained at mulids, cultural events and other festivities. She would teach the trade to family and those wishing to enter from the 'outside'. An Usta took care of all the business from negotiating to dances and songs performed and the most importantly the reputation of the group.

- Fath — from the Arabic verb 'to open'. Dancers were encouraged to sit with patrons and encourage them to drink (open bottles). This proved very profitable for the owners of the nightclubs. The dancers would receive a percentage of the alcohol they and their admirers consumed. Providing a greater source of income than the measly sum paid for dancing, nightclub owners had trouble getting the dancers away from the tables to dance! The ugly scenes that ensued from admirers thinking their attentive female companions would continue on into the night with them, left the profession of dance in further disrepute.

- Early 20th C onwards

21st Century

The most pressing challenges today in the preservation of the traditions of dance and music are:

- The socio/eco/political and religious developments resulting in a steady decline of the tribal and family structures that had preserved the traditions of these artists for centuries.

- The lack of written material and documentation due to the passing on of the traditions within the family/tribe.

It is important to note the dance is not religious in context, but it is a secular theatre art form which conveys all the form and beauty of a rich and colourful heritage. It does not necessarily favour any particular period, but rather draws from the history and heritage of the millennia, the extraordinary musical heritage, the people and their traditions, and the inspirational and transformational energy of the land itself.

Egyptian Dance has many strata and influences to explore.

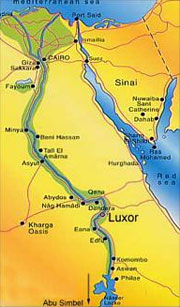

Egypt's unique heritage includes 3 main geographical influences: Arabia, the Mediterranean and Africa, and also 4 historical and cultural/religious influences: Pharaonic, Greco-Roman, Coptic, Christian and Islamic. Egyptian ethnic musicology is also subdivided into six regional areas that run the length of the land.

The three main forms under the umbrella of Egyptian Theatre Dance are; Sha'abi (Folk), Baladi (Urban Folk), and Sharqi (Classical). A new and dynamic Contemporary form has also recently evolved which allows fresh and exciting exploration of the intricacies of Egyptian music.

Sha'abi — Folk

Sha'abi — Folk

Baladi — Urban Folk

Baladi — Urban Folk

Raqs Al Asiah

Raqs Al Asiah

Contemporary Egyptian

Contemporary Egyptian

Egyptian Sha'abi (folk) dance is influenced by four regional subdivisions: Fellahin (farmers/peasants), Nubi (Nubian), Bedawi (Bedouin) and Sa'idi (Upper Egyptian). These four cultural folk traditions are grouped under the single heading of Sha'abi (folk).

However it is the Sa’idi tradition of Sha'abi, which even today exhibits clear links with Egypt's pharaonic past, and therefore provides the tenets of Egyptian Dance.

Some of the qualities conveyed in Egyptian Theatre Dance are dynamism, earthiness and power - yet it is elegant. Its primary expression is abstract rather than interpretive, the distinctive line and form of the dance identifies the culture, whilst the elements of 'al gharizah' and 'al fitrah' provide dynamic range and depth.

Despite such a long and diverse heritage, a strong thread of continuity runs through all Egyptian expression. North to South, East to West, past to present - the 'black land' is bound to the Egyptian people and the people to one another.

It is at once majestic, mythical, timeless - yet earthy, present and pulsating in the 21st Century, perhaps it is this heady mix conveyed through the movement and music that makes it so compelling to the observer and performer alike. Once bordering on extinction, the tenets and form of Egyptian Dance have been reclaimed for posterity, resulting in a beauty of line and depth of expression that truly conveys the elegance, dignity and power of an extraordinary heritage.

Copyright Juliet Le Page 2006

Egyptian Elementals Dance and Movement delivers an appreciation of culture, history and music combined with specific dance training, which is essential in depicting those qualities which transcend a sequence of steps to music.

Back to Home or Back to Culture

Other articles coming soon- About Baladi

- About Belly Dance