Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Egyptian Dance?

Raqs Al Asiah

Raqs Al Asiah

Egyptian dance is influenced by four regional subdivisions: Fellahin (farmers), Nubi (Nubian), Bedawi (Bedouin) and Sa'idi (Upper Egyptian). These four cultural traditions are grouped under the single heading of Sha’abi ('folk'). Other influences include Pharaonic, Copt, and Islamic traditions. Two thousand years of successive occupation and the resultant socio/economic and political upheaval have also impacted on the dance. However it is the Sa'idi tradition that still holds evidentiary links with Egypt's pharaonic history, and therefore it provides the foundation principles and structure which distinguishes Egyptian dance.

Read the complete essay; About Egyptian Dance.

What Is Belly Dance?

'Collette' from Reve d'Egypte C1907

'Collette' from Reve d'Egypte C1907

The generic 'Belly Dance' or 'Middle Eastern Dance' found in restaurants, nightclubs, street festivals, cabaret, etc., has become synonymous with Egypt principally in the last 100 years, however it owes more to the 'Orientalist' perspective and commercial expediency. For clarity on the development of Belly Dance and why it is has been accepted so readily worldwide read 'About Belly Dance'.

Does The Dance Have Any Religious Connotations?

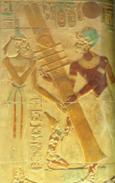

Tahtib, Ancient Martial Art

Tahtib, Ancient Martial Art

Egyptian Dance is not religious in context but a secular theatre art form with some primary source reference to antiquity. It also references many aspects of the history of Egypt including movement principles of the Sufi, Sa'idi and Nubian tradition.

It is important to note that to date, a link between Belly Dance and ancient Egyptian ritual has not been substantiated by scholars. The 'Goddess' concept is a Western perception. If you want to know more see, About Egyptian Dance, or About Belly Dance.

What Is The Costume?

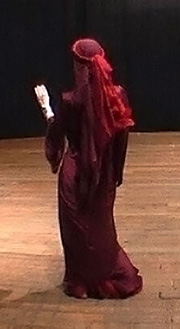

Juliet Le Page

Juliet Le Page

Costuming is inspired by the traditional clothing still worn throughout Egypt, and therefore we do not dance exposing flesh or use excessive dangles, baubles and coinage. These additions simply detract from genuine artistry and form. In fact they were specifically added for the purpose of attracting attention, and not to enhance any dance qualities.

Why Wear The Head Scarves?

Working in the field

Working in the field

Picture: Caroline Chevat

The head wear worn in Egyptian Dance is based on traditional secular Egyptian dress. The manner in which the scarves are worn and types of scarves/veils are not a reflection of any religious teaching or practice, and we do not cover the face. Throughout Egypt the simple cotton head scarf is worn to protect the hair from heat and dust during the working day, particularly by the Fellahin (peasants/farmers), and also in the Baladi quarters. In Egypt, this square cotton scarf is called a mandeel, and in the dance it is used primarily for Egyptian Sha’abi (folk) interpretation. The Tarha (veil) is often used in Baladi.

How Is This Good For My Body?

The Djeb Pillar, symbol of strength and stability.

The Djeb Pillar, symbol of strength and stability.

In this training program the aligned body works with gravity and not against it – which means you dance stronger for longer. Benefits/improvements begin to become apparent within the first 5 weeks. The focus on full physical integration and breathing techniques means that your posture and strength is constantly improving. I have witnessed some inspirational postural/fitness transformations during my time as a teacher.

It is not necessary to attain performance standard to experience the many benefits this dance form affords. It has been proven time and again that regular attendance to class delivers substantial improvement in physical fitness, and other benefits that have to be experienced to be believed! Fluid integration, functional strength and postural alignment cannot be achieved solely through isolated training/movement - even with the best technique.

See Egyptian Elementals Dance and Movement — Testimonials or Fitness Benefits — the results speak for themselves…

Awalim

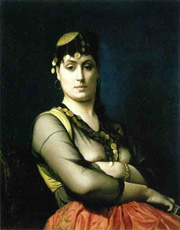

'An Almeh' - Jean-Leon Gerome

'An Almeh' - Jean-Leon Gerome

Thank you for your question Elizabeth; to my knowledge there are no books available on the Awalim as a topic complete. The Awalim are referenced in a fascinating and eclectic collection of notes/essays/books and general travel writings of visitors from the West to Egypt, particularly during the late 18th to early 20th Centuries.

Awalim translates as 'Wise or learned' women (Almeh - singular). They were known to have an encyclopaedic knowledge on everything to do with the Arabic/Egyptian musical heritage. They could play instruments and sing with a repertoire that spanned Egyptian/Arab history. They also recited poetry and were renowned for composing songs on the spot to suit a particular mood or occasion. Their knowledge was passed on orally, which was a contributing factor to the demise of their kind. It is clearly stated they did not dance (musicians/poets/singers only), although it is suggested they may have danced a little at women only gatherings - this has not been formally substantiated, and my research suggests extremely unlikely. Originally they were held in the highest esteem, possibly because they did not dance or perform in public places. However, by the late 19th Century the appellation ‘Awalim’ had gathered other, far less flattering connotations (i.e. synonymous with Ghawazee or prostitution) as explained in my essay 'About Egyptian Dance'.

We are fortunate that at least the Arab/Islamic Classical musical tradition was eventually transcribed for posterity, although for centuries that too was only taught orally – literally from the mouth (and instrument) of the teacher to the student, who was required not only to have exceptional talent but also an unfailing memory. Since we know that the true Awalim would not even sing and play an instrument for men unless separated by a screen, it is reasonable to conclude that most of the popular Orientalist artistic representations i.e. (Gerome) that claim to depict Almeh are inauthentic. It is highly unlikely a true Almeh would happily agree to pose or perform for an ‘infidel’, let alone in a costume that left little to the imagination. However, disenfranchised women, courtesans, dancers and/or prostitutes touting for work (and their very survival) certainly would oblige – as indeed they did. These Orientalist depictions (pictured), greatly undermined the reputation of the true Almeh. Westerners consequently travelled to Egypt specifically seeking such women for licentious gratification – and they did not have to look far to find an 'Almeh' to oblige.

Ancient Soles

Despite the fastidious pride Ancient Egyptians took in their wardrobes and appearance, (so clearly demonstrated to us through the time portals of Egyptian art and extant papyri), - nearly all Egyptians went barefoot - even on the most formal of occasions. It is interesting that even the elite of Egypt mostly went barefoot, despite a sandaled foot being sign of wealth and privilege. One was not permitted to wear sandals in the presence of a superior, so it would follow that in the presence of Pharaoh all appeared barefoot. Sandals became increasingly popular during the New Kingdom, but even so, barefoot still 'ruled' in the land of the pharaohs. Thankfully, sandals for daily use were made of palm-fibre, papyrus or sometimes leather, (see picture right). For information on how to access the complete article 'The Beauty of Being Barefoot' visit the blog.

If you have a question please email juliet; juliet@eed.com.au